AB Direct - Steers

Rail: ---

AB Direct - Heifers

Rail: ---

US Trade- Steers

Rail: 290.00 (IA)

US Trade - Heifers

Rail: 290.00 (IA)

Canadian Dollar

0.02

ABP Research Showcase Highlights | Evaluating Johne’s disease control options

This is the fifth in a series of articles highlighting a selection of ABP-supported research projects that were featured at our Research Showcase in February 2023. Find the previous articles here.

With no vaccine or treatment available, preventing and controlling Johne’s disease in livestock comes down to biosecurity measures and testing.

However, testing for Johne’s has its challenges, said Cheryl Waldner, professor and NSERC/Beef Cattle Research Council Industrial Research Chair in One Health and Production-Limiting Diseases at the University of Saskatchewan.

“We just need to understand what the issues are and try to keep those issues in mind and consider them when we’re trying to optimize the best way to use those tests,” Waldner explained at the Alberta Beef Producers Research Showcase in February.

The first issue with testing is the disease’s long, silent incubation period, in which the animal has been infected but isn’t yet shedding the bacteria.

“There’s really very little that we can detect in terms of visible signs of infection in the animal. So we basically could have a calf that gets infected in the first couple of weeks of life that doesn’t actually start to shed until they’re two or three years old,” said Waldner, adding that signs of the disease may not be present for several years after infection.

The second issue is that infected cattle shed the bacteria inconsistently, so they may not be identified through testing.

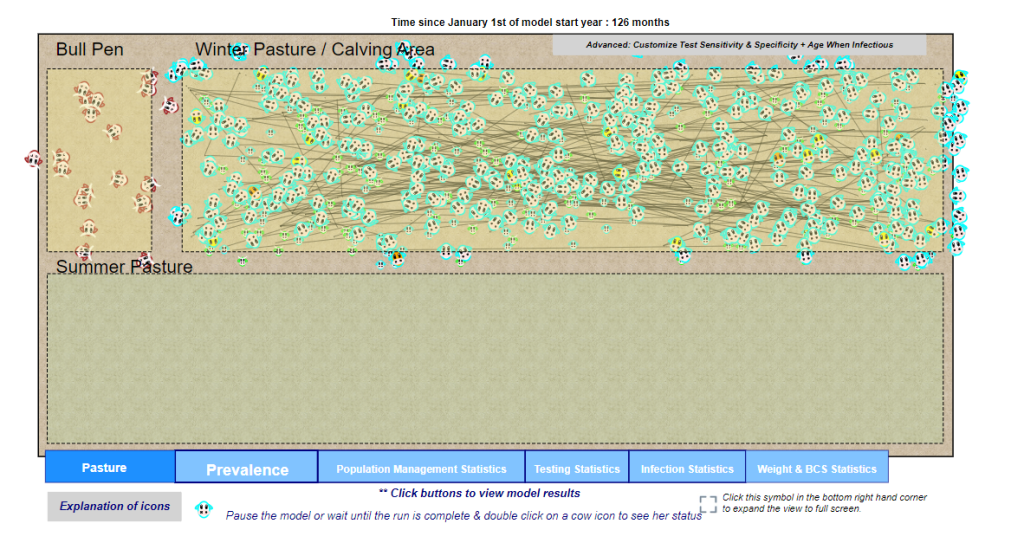

With these limitations in mind, as well as the cost of testing and questions about the frequency and type that should be used, Waldner and other researchers developed the Johne’s Testing Decision Tool, now available on the Beef Cattle Research Council (BCRC) website. The team used anonymous data from Western Canadian cow-calf herds to build this model, which helps producers compare different testing options through a simulation customized to their own herd.

“It’s not a crystal ball. Even if you put in the data that’s specific to your herd, it’s not going to give you a perfect prediction, and it’s not intended to do that. It’s intended to help you rank the possibilities and see what might work,” said Waldner.

How to use the tool

To begin, producers enter details about their herd, such as size, current Johne’s risk, and whether replacement females are raised or purchased. They can select different types of tests, as well as which animals will be tested and how frequently they’re tested.

Using this information, the tool runs simulations that provide the potential outcomes of different testing and disease management strategies. The potential outcomes are illustrated as graphs to show disease progression in the herd and how that may affect factors such as weaning weights, cow numbers, and culling rates over time.

“The big thing this tool does is help us deal with the uncertainty. We know the various tests can work, but we don’t know exactly how well, and there’s some uncertainty in terms of those numbers. We know the cows start to shed, but we don’t know exactly when,” said Waldner.

The tool also reflects the realistic, random nature of disease transmission, including an error bias to show the variability of the disease prevalence.

“There’s a lot of chance in the transmission of infectious disease, so we want to make sure that we’ve accounted for that variability,” she explained.

“We’re not just going to get the same answer every time something happens in real life. Equally, we don’t want exactly the same answer every time we run the model because that wouldn’t mimic real life. We want that model to capture the uncertainty.”

Finding the best testing options

As part of this project, Waldner and the other researchers used the tool for their own study on the best testing options for Johne’s control. Results of this study are available in this ABP fact sheet on improved Johne’s management.

“We basically ran the tool 10,000 times for each question, asked what happens, and did some did some stats on that to pull it all together,” she said.

Based on the simulations, they found that the best option to reduce disease transmission is to PCR test the entire herd every six months or every year. This is also the most expensive option, and Waldner noted that while some producers are unlikely to choose this method, those who want to get it out of their herd as soon as possible may find it valuable.

“This does have a potentially reasonable chance of success. Of course, there’s other things you can do. If you combine with that with management and a very strong heavy hand on management, that’s going to make it even better.”

The study also highlights other testing and culling options producers can consider that are likely to reduce the prevalence of Johne’s disease over time, using either pooled fecal tests or blood ELISA tests.

This study was partially funded by Alberta Beef Producers. To learn about more ABP-supported studies and find fact sheets for completed and in-progress projects, visit our Research and Development webpage.

Leave a Comment

Add abpdaily.com to your home screen

Tap the menu button next to the address bar or at the bottom of your browser.

Select ‘Install’ or ‘Add to Homescreen’ to stay connected.

Share this article on

About the Author

Piper grew up on a purebred cow-calf operation in Southern Alberta, and she studied English and history at the University of Alberta and journalism at the University of King's College. She has written for industry publications for more than a decade and is currently the Digital Content Specialist for Alberta Beef Producers.