AB Direct - Steers

Rail: ---

AB Direct - Heifers

Rail: ---

US Trade- Steers

Rail: 290.00 (IA)

US Trade - Heifers

Rail: 290.00 (IA)

Canadian Dollar

0.02

Rethinking the packing sector

Wow, have you looked at the price of a steak lately? Canadian retail beef prices are at the highest level in history, inflating over 20% a year. A good steak or roast can cost $25-50 in the store; can you believe it?

That is for an unbranded commodity product sold from a largely undifferentiated commodity system, in a major retail store. These are not the niche butcher or local variety retail store prices. Prices are even higher there. So why is every cattle person I know grumbling about margins?

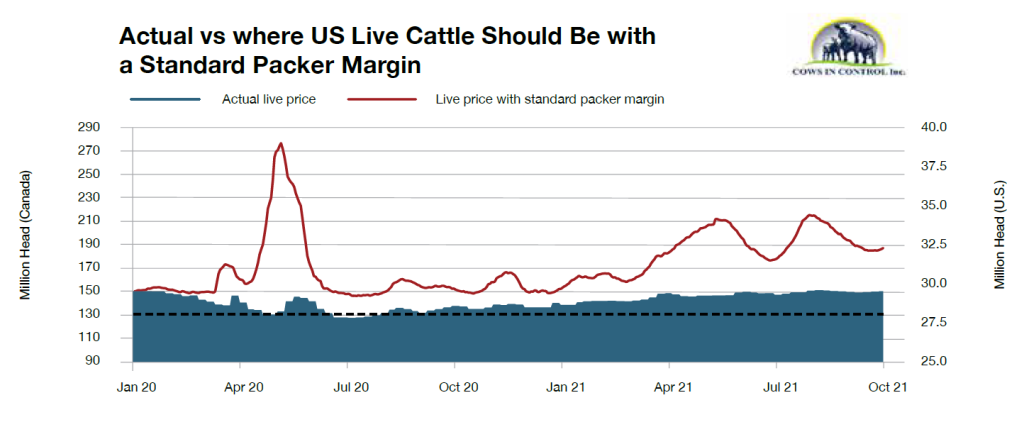

Beef cutout prices rose 38%, yet our fed cattle prices are at the same level as they were at the end of 2019. We may need to rethink our system here.

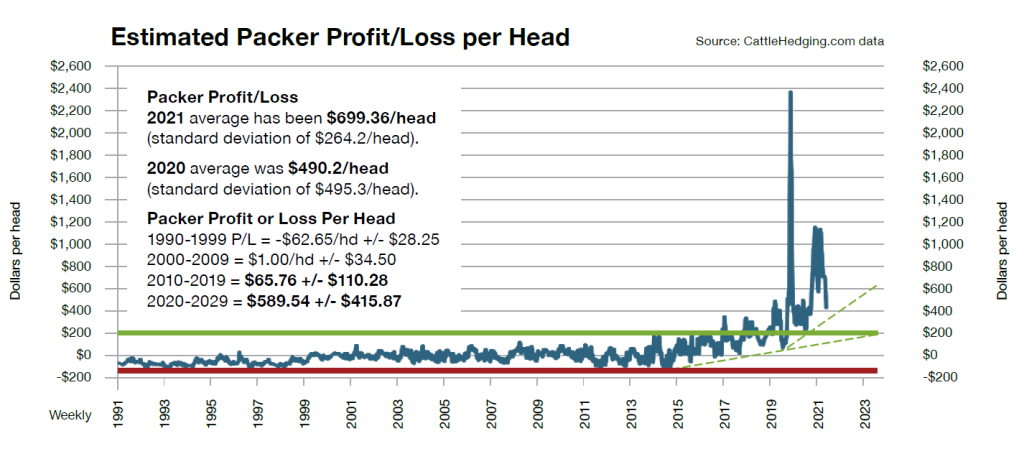

One U.S. packer reported Q3 earnings for 2021 were up 93% year on year. Another (a private company that stopped publicly reporting its earnings in 2020), just revealed its biggest profit in its 156-year history; up 64% year on year. A third reported Q3 2021 earnings growth of 146.9% year on year. Below is a long-term chart of packer margins (courtesy: cattlehedging.com) in the U.S. I think we can see the trend.

The beef packing industry has evolved into an oligopoly system with four major packers in the U.S. controlling 85% of total supply and two major packers in Canada controlling 75-80% of the nation’s supply. In the past two years we have seen drastic pullbacks in fat cattle prices during the plant fire in Holcombe, Kansas; or the JBS ransomware attack; or, of course, the COVID shutdowns in 2020.

Does it make sense from a food security standpoint in Canada to have two foreign-owned, standalone facilities that handle 35-40% of the total beef supply each? One COVID outbreak, plant strike, fire or whatever, and 40% of the beef supply goes offline.

A contrary example would be in the country of Uruguay. Uruguay has a land mass 1/3 the size of Alberta, a similar number of cattle and similar processing capacity as Canada, but has 27 federal exporting, regionally distributed plants. It exports 75% of its product outside the country, fully traceable. This model is possible if the industry wills it. I am not sure that our industry has been “willing it.”

Packer margins (value of the beef carcass minus the value of the live fed animal) in the U.S. before COVID averaged $150-250 per head. They got as high as $2700 during COVID, and are around $700 today. Our fat prices since 2019 have been flat in the U.S. and Canada. If we used pre-COVID packer margins, fat prices would be $791 CAD per animal higher than current prices.

There is our producer margin issue.

Plants will argue that costs have risen due to COVID PPE measures. Let’s remember that the packers in Canada were awarded $77 million during 2020 to address COVID measures. Then look again at the 2021 corporate packer profit growth.

Consumers are begging for more connection to their food; to know where it comes from. The large plants do not custom process and have no individual farm to consumer brand programs. If producers want to develop niche products, they sorely lack processing capacity to develop these programs as most of the smaller plants are provincial only, or small federal plants are booked with several months waiting lists.

Many advocates in our beef industry are defending the big plant systems as they suggest smaller plant initiatives have been largely unsuccessful in the past, costs are higher in the smaller plants, and access to temporary foreign labour has been a challenge. To keep beef affordable and competitive with pork and chicken, they say we need cheap, large plants. Hmm.

Large packer margins of late have not kept beef cheap. A little competition would help.

If our primary focus is to go head-to-head with commodity pork and chicken on price, we will continue to lose market share. Could beef be sold more like wine ꟷ a high-quality product differentiated by breed, region, how it is raised, branding, by valued connections between the producer and the consumer? That’s more difficult to do in a big plant system. It will take smaller, regional custom plants to develop that type of market connection, and value add to our prices.

Let’s look at the cost benefits of smaller plants. Firstly, they can be regionalized, closer to where the production occurs, thereby reducing the freight and shrink costs as well as time that cattle stand on trucks being hauled to plants. Good from an animal welfare standpoint, but also for beef tenderness, which is tied to animal stress. Long truck rides are stressful. Secondly, there are savings in having less food, biosecurity and cattle price risk in a small plant going down compared to mega plants where 40% of the total national supply can go down in a single plant event. Thirdly, there is the value creation of custom processed, ranch to retail marketing programs. Lastly, what is the security and optics value of locally owned food processing over foreign owned brands and processing?

So how do we get more of these smaller plants? Firstly, our industry needs to promote them; lobby on their behalf. Secondly, streamline the federal permitting and regulation process to get them started. Anyone trying to start a plant has run into that hurdle. Thirdly, expedite and seek federal assistance on temporary foreign labour availability, as well as local labour promotion in these smaller plants. Fourthly, protect smaller start-up plants from predatory pricing tactics by the majors during start-up periods. Fifthly, government and industry need to develop more national and local plant management training and meat cutting schools. We need to develop the human resources needed to operate these smaller plants. And lastly, producer plant initiatives have often failed due to lack of committed supply, capital, and/or professional experienced management. Harmony Beef Plant in Balzac has been an example of a success story that made this a priority from the start.

The benefits of source verified ranch to retail product from custom plants can easily compete with the cost efficiency advantage of larger plants. Let’s not do away with larger plants, but can we support and look at alternatives as an industry? That will differentiate Canadian and Alberta beef from its competition and allow beef to sell more like wine. “I’ll have the XX breed, raised in the XX region of Alberta by the XX family ranch, raised sustainably by doing XX, please.”

This article was first published in Volume 2 Issue 1 of ABP Magazine (January 2022). Watch for more digital content from the magazine on ABP Daily.

Alberta Beef Industry Competitiveness Study

A study, led by Alberta Beef Producers, alongside the Alberta Cattle Feeders’ Association, Canadian Cattlemen’s Association and the Government of Alberta, has launched that will assess risks and overall competitiveness of the province’s beef industry.

This study will enable the industry and government to better understand the needs of the sector from a whole supply chain perspective. It will shed light on the best approaches to build capacity, diversify and enhance the resiliency of Alberta’s beef processing sector.

The study will involve an extensive survey of current operations, of all sizes, to underscore common and unique challenges to better understand barriers to growth. Additionally, price and market transparency will be explored to identify critical data points indicating when markets are operating efficiently and potential options for when supply chain dynamics become suboptimal.

The goal of this study is to help build a set of recommendations to increase capacity focused on the size of the operation, geographical need and cattle requirements. A strategy will be developed that will focus on maintaining, expanding and attracting beef packing capacity in the province.

Leave a Comment

Add abpdaily.com to your home screen

Tap the menu button next to the address bar or at the bottom of your browser.

Select ‘Install’ or ‘Add to Homescreen’ to stay connected.

Share this article on

About the Author

Ryan's career has involved managing and operating a large historic family ranch as well as building one of Canada's largest multi-ranch cow/calf programs. His current company is called Cows in Control, a company designed to focus on providing financial and risk management advice to farmers to protect the value of their commodities and inventories. Ryan has an MBA from Queen's School of Business, a finance degree, and over 25 years in the ranching and farming business.