AB Direct - Steers

Rail: ---

AB Direct - Heifers

Rail: ---

US Trade- Steers

Rail: 290.00 (IA)

US Trade - Heifers

Rail: 290.00 (IA)

Canadian Dollar

0.02

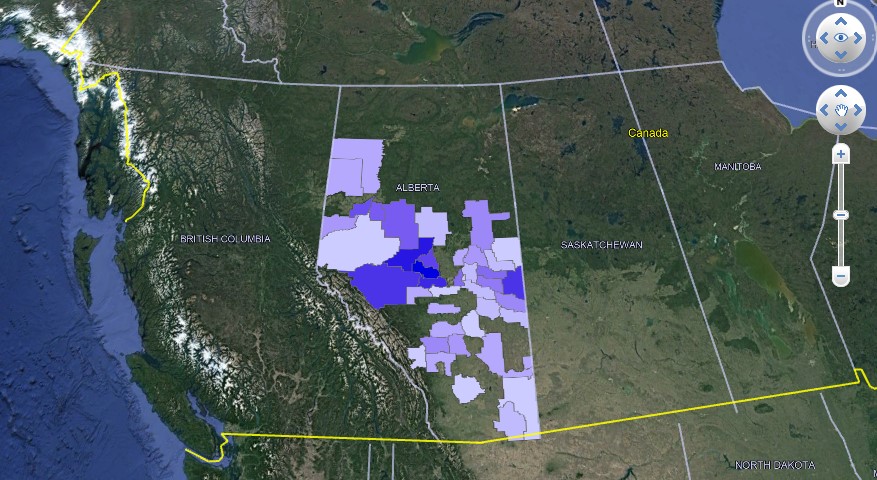

Wild pig distribution and eradication on the prairies

When wild boar were first brought to the prairies, experts suggested crossing them with domestic pigs for a bigger, more reproductive animal. Unfortunately, some of the traits that make them great farm animals, also make them a wildly successful invasive pest.

According to Dr. Ryan Brook, wild pig occurrences occupy just over one million square kilometres in Canada, with 99.4 per cent of occurrences on the prairies.

Brook is an Associate Professor at the University of Saskatchewan. He’s been researching wild pigs for over a decade, and calls them “the most successful invasive large mammal on the planet.”

They’re long-lived and they reproduce quickly, with six young per litter on average, he says, with multiple litters per year.

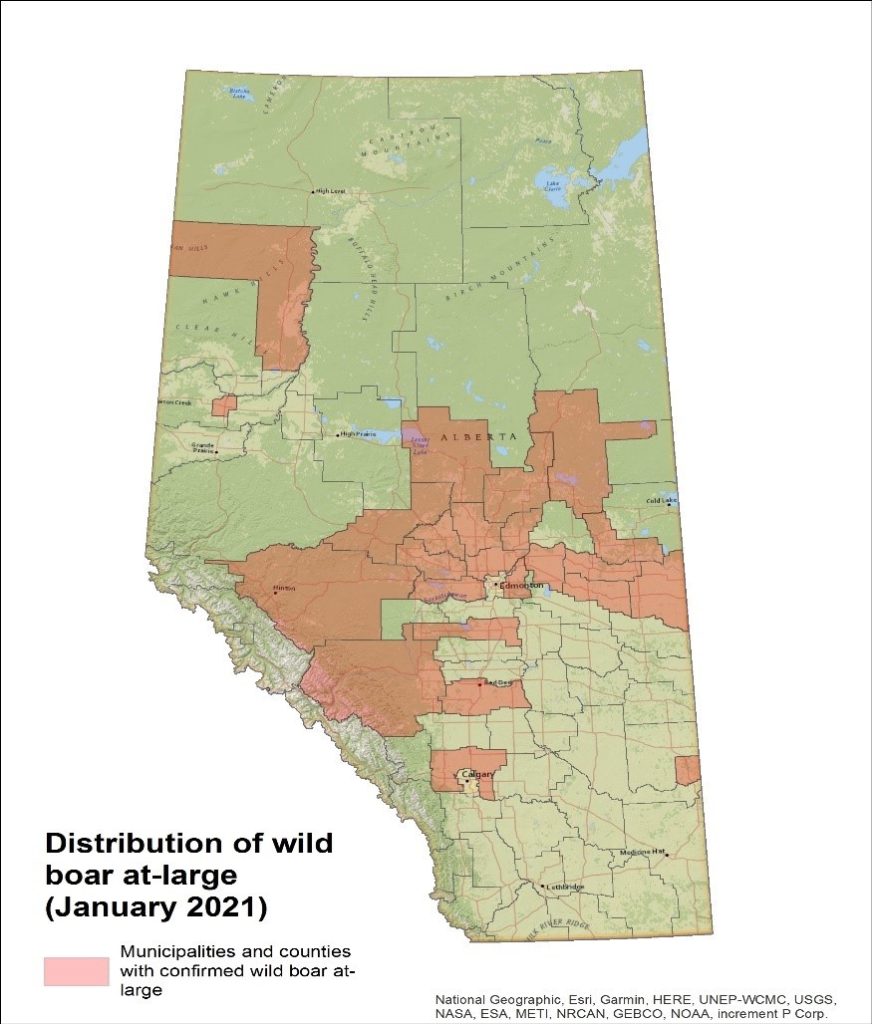

Report wild boar at large in Alberta

And, for such a large animal, they’re incredible elusive.

“The biggest challenge I think we have is wild pigs are out of sight, out of mind. They’re around, they’re widespread, but people are not seeing them,” says Brook. “For a long time it sort of felt like studying Bigfoot or something, because nobody believed they really existed.”

If it looks like a pig

Brook and his team choose to refer to pigs at large as simply ‘wild pigs.’

“Not all animals running around outside in the wild are actually wild boar,” says Brook. “In fact, it would be very rare to see a pig outside of a fence in Canada that’s a true ‘wild boar.'”

That’s partly because many of the hairy pigs in the wild have domestic pig genes. And also because there are free-ranging feral domestic pigs and pot belly pigs.

But the reaction to any pig sighting should be the same — report it (details below).

“If it’s outside of a fence, and it looks like a pig and oinks like a pig, then call that in for sure.”

Damage caused by wild pigs

Wild pigs cause many different kinds of damages, including:

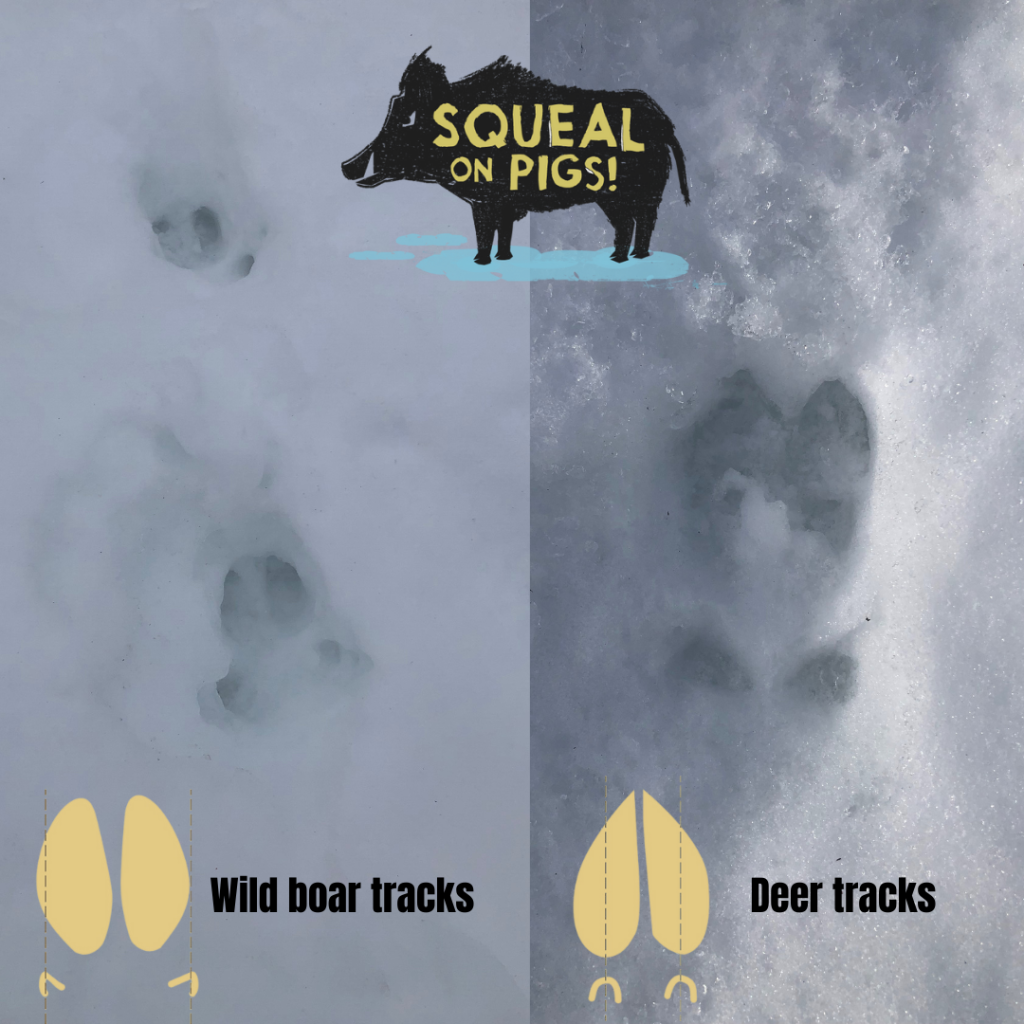

- Crop damage – Brook suspects crop damages claimed for elk and other species may actually be caused by pigs. Watch for torn-up ground, and identifiable tracks.

- Livestock harassment – In some cases, livestock harassment goes beyond stress. “Cattle are being pushed away from their water source…to the point where animals are so distressed that the producer actually has to move the watering area and feed somewhere else, because cattle won’t come back,” says Brook.

- Disease – While we know wild pigs have the potential to vector disease, and threaten the entire pork industry, Brook says “we don’t really have a sense of what’s out there.”

- Food and water quality – Brook says salmonella and E. coli-based recalls in the U.S. have been linked to wild boar contamination in vegetable crops.

Dr. Ryan Brook joined us in the second segment of Episode 4 of The Bovine. Click the ‘list’ icon on the player above, or skip to 21:26 to hear that interview. (Or better yet, download it and listen to the whole thing, wherever you want!)

Inventing the future

According to Brook, Alberta is at a cross-roads, but there is still the possibility of eradication in the province.

Unfortunately, control measures are complicated. Pigs tend to out-reproduce shooting, and become more nocturnal as they’re hunted, he explains.

“Normally on average, at most you’re seeing 23 percent hunter success. So if there’s a sounder…if hunters try to shoot them, they’ll almost never get them all.”

“While sport hunting has been a great tool for a lot of wildlife management over the last hundred years, it just simply does not work for pigs. And unfortunately, it makes the problem worse. Shooting at groups breaks them up, and it…spreads them across the landscape and makes them that much more elusive and hard to find.”

“As we say, ‘you can not barbecue your way out of a wild pig problem.'”

Brook says the “path forward to success” is through whole-sounder removal.

This is often done through baiting and trapping the whole group.

Another technique Brooks says is very successful is the “Judas pig technique.”

“So you capture a wild pig, put a collar on it and follow it. And nothing finds wild pigs better than a wild pig.”

Brooks says while it hasn’t taken off for any other provinces, there’s hope it will.

including the significance of the problem,

and how whole-sounder trapping works.

Reporting wild pigs in Alberta

If you see signs of wild pigs in Alberta, or damage they may have caused, report them through EDDMaps, by email, online, by calling 310-FARM, or by contacting your local municipality.

Learn more about wild pigs from Alberta Invasive Species Council.

Recent changes in provincial regulations

There have been recent announcements regarding wild pig control measures on the prairies.

Saskatchewan

In March, just ahead of our interview with Dr. Ryan Brook, Saskatchewan announced enhanced measures to control feral pigs, including:

- The development of regulations for licensing existing commercial wild boar farms and imposting a moratorium on any new farms.

- The development of regulations under The Pest Control Act to specify monitoring and control efforts and public obligations to report.

- The doubling of annual funding for the Saskatchewan Crop Insurance Corporation (SCIC) Feral Wild Boar Control Program for surveillance and eradication efforts.

Alberta

And following our recording, Alberta announced:

- Wild boar damage is now included in the Wildlife Damage Compensation Program administered by the Agriculture Financial Services Corporation (AFSC).

- Expanded surveillance and trapping.

- Modified bounty programs, including:

- A Whole Sounder Trapping Incentive Program is running from April 1, 2022 to March 31, 2024, wherein government-approved trappers will be compensated $75 per set of ears per sounder in participating municipalities. Landowners who work with approved trappers will also be eligible for compensation.

- A Wild Boar at-Large Ear Bounty program is running from April 1, 2022 to March 31, 2022, where hunters who turn in wild boar ears will receive $75 per set in participating municipalities.

Leave a Comment

Add abpdaily.com to your home screen

Tap the menu button next to the address bar or at the bottom of your browser.

Select ‘Install’ or ‘Add to Homescreen’ to stay connected.

Congratulations on constructing a puzzle for the ages (or the aged). In reading your piece a number of times, I determined that I would have to guess when the interview with Dr. Brook took place (sometime between March and just before April fool’s day, 2022?). Not that too much turns on that because the Alberta Government is clearly not listening to what Dr. Brook has said and continues to say about the feral pig (wild boar) problem.

They clearly listen to their rural constituents as evidenced by the compensation program for wild boar damage given to Alberta farmers – It would be interesting to see the process for adjusting those claims.

If I understand Dr. Brook’s comments, trapping the entire group of pigs stops that group of pigs from proliferating, and trapping all the groups of pigs in a defined geographic area eradicates them from that area until…

a pig or two or three that hightailed it away from an attempted mass shooting enters or re-enters the geographic area and a few short months later, we have another infestation on our hands…

only this time, the pigs have become nocturnal. Some people are attributing intelligence to the pigs – I think it’s probably good enough to say that before their whole family got shot to pieces, they enjoyed daytime picnics of whatever their paths came upon, but afterwards they tend to dine continentally.

Context can usually be relied – in the above paragraph it communicates that the pigs almost exclusively confine their activities to periods of darkness, but not always. On the other hand, the article misuses the word ‘tend’ in the sentence below.

“Unfortunately, control measures are complicated. Pigs tend to out-reproduce shooting, and become more nocturnal as they’re hunted, he explains.”

In fact, pigs always out-reproduce shooting them (i.e. that’s not a tendency, it is a fact), and in fact, it is the attempted shooting of them tends to make control measures “complicated”.

I have only looked into the feral pig problem recently, whereas Dr. Brook has looked into it for 10 years or so. Based on the track record of the Alberta government for the last 30 – 40 years, I am not surprised but continually disappointed in its demonstrated inability to figure out who knows what about what and shape their policies around that advice.

Here’s the recipe. We’ve known about the problem for many years, we have had the opportunity to see what has happened in other areas, we have had the opportunity to see what control measures have met with what level of success, and now we have the opportunity to put that knowledge into action.

So what does the government do? They announce they’ll pay $75 per set for ears from trapping groups of pigs, but, I guess the devil’s in the details, if the trapping exercise doesn’t get them all, the ones that get away become more wary and harder to trap. I guess it all part of the “everybody get’s a gold star for trying” mindset. You set out with an objective, you failed to achieve it, but we’ll pay you anyway, even though you made the next trapper’s job harder. What part of the title of the program did the payor miss – oh, right, the word “Whole”. Missing words tends to render communications more or less ineffective.

In the very next sentence they score another own goal by extending the $75 bounty per pair of ears for hunting. It is not as if Dr. Brook couched his advice in a foreign language or was in any way unclear. Hunting not only doesn’t work, it makes it worse.

It is astounding that a whole government department can put their heads together and come up with this kind of nonsense. If I were Dr. Brook, I would think twice about investing any more of his precious time talking to the interviewers at the Bovine.